How Geospatial Data Drives Insight for Bloomberg Users

(GarryKillian/Shutterstock)

Stockbrokers and other Wall Street professionals who use Bloomberg terminals are always on the lookout for an edge. Increasingly, that edge is coming in the form of geospatial data that describes the movement of people and goods – as well as natural events like hurricanes and viral pandemics — through space and time.

When US Air Force veteran Bobby Shackelton arrived at Bloomberg about five years ago, he found some pretty basic uses of geospatial data in the Bloomberg Terminal, that all-important source of news and data relied upon by thousands of individuals who make their living trading on information.

For example, commodity traders used geospatial data to understand the number of oil tankers under sail in the ocean at any point in time, which describes the short-term supply of that crucial commodity. But aside from a few niche cases like that, there really wasn’t much going on with geospatial data at Bloomberg.

So Shackelton, who helped set up radar installations in the Air Force before building geospatial data solutions at what would become S&P Global Market Intelligence, set out to build a full-stack mapping solution for the Bloomberg Terminal. That offering, called MAP GO, quietly debuted about two years ago.

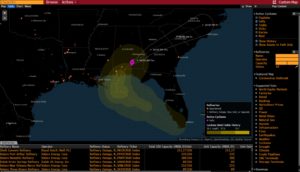

As its name suggest, MAP GO features a map. If you happen to be a map buff, then the application was fun and exciting. Maps, after all, are elegant devices for delivering useful information. But maps–even digital ones that are constantly updated like MAP GO–are relatively static things. They are great at delivering a snapshot of the world in a top-down view, but that doesn’t necessarily translate into decision-making bliss.

That was the dilemma that Shackelton struggled with–how to make the geospatial data more actionable than just displaying it in a map.

‘It’s Just a Map’

The typical geospatial workflow would start off with a client going into MAP GO to create a map for an investor presentation, or to come up with a novel idea to trade on.

“They go in, they explore the map, and then they go off and look and research the company a bit more,” Shackelton tells Datanami. “This is the exciting nature of maps, but it’s also the challenge that I faced when people say ‘Hey, it’s just a map. Who cares?’”

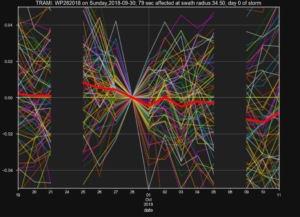

Bloomberg’s MAP GO app lets users visualize the impact of real-world events, such as a tropical storm (Source: Bloomberg)

The solution, it turns out, was separating the geospatial data from the map. The map would remain a tool for doing primary research and for investor presentations, but Shackelton realized that the geospatial data could have a greater impact if it wasn’t tied to the map.

“For years, our financial clients, even the really techy ones like hedge funds and quants and data scientists–they struggled with geospatial data because it was static, because it wasn’t tagged to a company, because it didn’t have history tagged to it,” Shackelton says. “But the infrastructure and technology that my team has bult over the years has streamlined that to be done in real time. So now we can make those connections and associations and insights delivered, just like that.”

Geospatial data is another form of alternative data, and it’s finding its way into the MAP GO application. In addition to weather, Bloomberg is constantly gathering and data on companies, commodities, and of course the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bloomberg Terminal customers can access these packages of geospatial data, and have it delivered in various forms: straight tabular data, text alerts, or even delivered in a summarized form, thanks to natural language generation.

It’s all about combining data in a way that turns a static information source into a dynamic one, Shackelton says.

“If you think about a building, your house, or the location of factories – they don’t change. That is a static data set,” he says. “In the financial world, they’re all about time and temporal back testing and analysis. So what I can do using geospatial tools is frankly make any static data set dynamic. By connecting things like weather properties to a physical location that doesn’t move, I can now make that factory update all day long with weather attributes. So now I’ve introduced volatility or some sort of insight or signal to that previously static insight.”

Alternative Data

Geospatial data is a form of alternative data, and it’s being readily incorporated into the quantitative analyses at hedge funds and other groups looking for an edge on the market. With time-stamped and geo-tagged data flowing into the system, Bloomberg helps its clients get real-time insight into events happening around the world.

After assembling a relevant collection of geospatial data, data science teams will often back-test it against market signals, in the hopes of finding a correlation. If one is found, Shackelton says, the data science team will productionize the code and turn it into a systematic feed.

“So it goes from the process of finding the signal, showing it with a Sharpe Ratio or some study to the portfolio manger, who then says ‘Okay, let’s adjust our model and now that will be a new input,’ – again, without ever looking at a map,” Shackelton says.

Weather- and climate-related data remain some of the most heavily used alternative data sources in MAP GO. The data is used by investors, but it’s also used by companies hoping to better quantify their exposure to risk. For these use cases, companies are calculating their TCFD score, as defined by the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures.

“So not only are we getting the money-making side of trading and selling for investments, but we’re also getting, from a climate TCFD sustainability side, this climate impact for my companies and my portfolio,” says Shackelton , who was awarded the Achievement Medal and Outstanding Unit with Valor for his service during the Iraq War. “I’ve worked with the UN and several of the pilot groups in these banks to establish data and methodologies for this climate-related physical risk reporting.”

When the novel coronavirus emerged earlier this year, it provided another way to use geospatial data. Bloomberg has incorporated COVID-19 case data into its geospatial feeds, thereby providing its clients with a actionable signal upon which to trade or assess exposure. “It’s similar to weather,” Shackelton said. “Whether it’s a snowstorm or a fire or a virus outbreak, it’s impacting things geographically.”

Bloomberg Terminal clients could get a sense of supply chain disruptions resulting from the pandemic, Shackelton says. It also allows them to gauge a company’s or a region’s exposure to risk from COVID-19 by analyzing the density of the caseload in areas they operate. The pandemic has impacted the entire world, and its impact can be traced using geospatial, time-stamped data.

Looking Forward

Shackelton has accomplished quite a bit with his team over the past five years, but he’s convinced there’s room to do a considerable amount more, particularly when it comes to climate and weather data.

“I think the preiovus years we were just getting started and it’s starting to get into exponential growth mode,” he says. “So over the coming years, my plan is to peak that and then get to the full mass audience in the coming years, as we continue to quantify and understand the impact of climate and weather.”

MAP GO is available to all of the 325,000 users of the Bloomberg Terminal (Filatova Olga/Shutterstock)

The blossoming of open source technologies, such as TimescaleDB, Elastic, and CartoDB, as well as Jupyter and Docker, have certainly helped Bloomberg and provided the core building blocks that it uses to deliver its service. But one can’t discount the advantage of having the skills of more than 6,000 engineers at Bloomberg to tap into. Having a budget to go out and buy data sets that are of interest to customers also helps.

“There are a lot of niche one-off data providers in geo,” Shackelton says. “But what we’ve done here is we’ve brought a collection of seven different industries worth of data and company coverage.”

Instead of clients trying to assemble their own geospatial data collection, Bloomberg has given the 300,000 Bloomberg Terminal customers a good reason to use what Shackelton has built.

“I’m in a position to absorb the cost of generating it and spreading it across the whole industry that much better,” he says, “and, frankly, bring geospatial analytics to the mainstream that much faster.”

Related Items:

AI Opens Door to Expanded Use of LIDAR Data

The Data Science Inside the Bloomberg Terminal

5 Ways Big Geospatial Data Is Driving Analytics In the Real World