Björk Was Wrong About Human Behavior, Big Data Says

Icelandic pop superstar Björk might have had a hard time making sense of human behavior, as she sings about in the song of the same name. But when it comes to protests and cyber attacks, big data can accurately predict how people will behave, MIT scientists have learned.

|

|

| “If you ever get close to a human and human behavior be ready to get confused, there’s definitely no logic….” | |

There is little question that social media is affecting our lives in big ways. All over the world, people are immersed in their smartphones on a daily basis, texting with friends, updating Facebook timelines, and live tweeting 11 o’clock coffee breaks. “#venti 4 the lols!”

On a more serious note, we also see how social media is taking an active role in helping to shape world events. During the Arab Spring of 2011, people used social media to communicate, to rally around a cause and, ultimately, to overthrow the governments of Egypt and Tunisia.

The role that social media played in these events is obvious in hindsight. The big question is whether natural language processing on a massive scale can be employed to predetermine how large groups of people will behave.

In a paper titled “Predicting Crowd Behavior with Big Public Data,” MIT grad student Nathan Kallus says it can be done. He makes the case that, due to the fact that so much of our lives and public consciousness takes place online, that these online repositories can, in fact, be effectively mined for signals about where that group consciousness is headed.

To prove his thesis, Kallus got his hands on public data from more than 300,000 open content Web sources in seven languages. The sources ranged from mainstream news sites to government publications to blogs and social media. Because gathering all that information manually would be such a hard task, he enlisted the Web outfit Recorded Future, which has tools for parsing large amounts of data.

Armed with scads of social media data, Kallus did the hard work of translating the words into values that can be measured, and determining whether there is a statistically significant correlation between calls for protest (or threats of rioting or cyber attacks) and whether those events actually happen.

|

|

|

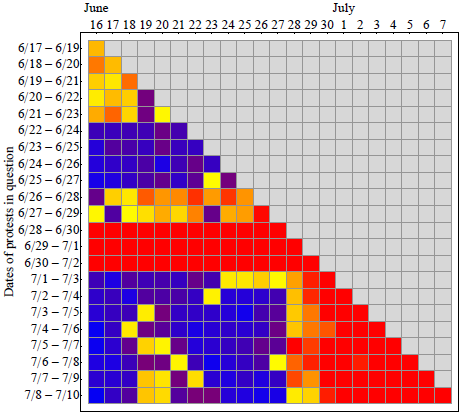

Predictions of protests in Egypt around the time of the coup d’état. Yellow to red mark positive predictions and blue to purple negative, with redder colors indicating more positive votes in the forest. Source: Nathan Kallus |

|

Kallus trained a random forest classifier with Twitter chatter from 18 Middle Eastern and African countries during the summer of 2013 (a period of time that saw significant unrest in the region). He tracked the rate at which “violent language” was used, and also tracked for “forward-looking” mentions of events that people are setting up (or trying to set up). Then he correlated it with “significant protest” events that actually took place.

He found a positive correlation between calls for protests on Twitter and actual protests in the real world. The predictive value of this approach declines the further out in the future you go. Trying to predict crowd behavior out beyond 22 days was not much better than “data-poor, predict-like-today” heuristic, he wrote.

Predicting protests isn’t just a novelty act, and has real-world uses, according to Kallus. For example, if mass protests are forecasted to occur, companies or organizations could ask their employees to stay home, and to take measures to protect their facilitates. Governments could also use the method to predict possible acts of cyber warfare against them, and take pains to beef up their cyber security in anticipation of attacks, or even preemptively address them, Kallus writes.

The paper can be downloaded from the Cornell University Library.

Related Items:

Discriminating Aspects of Big Data

Why IBM Watson Knows You Better Than You Think

Highlighting Business Signals on the Noisy Web