What Is Data Science? A Turing Award Winner Shares His View

Data Science Venn Diagram (Source: Drew Conway)

The phrase “data science” is used every day, including in this very publication. We feel like we have an idea what it is. But what exactly is it? For one answer, we turn to Jeffrey Ullman, who won the Turing Award in 2020.

“Where does data science come from?” asked Ullman, a Stanford University computer science professor, during his keynote address at the 27th ACM Special Interest Group on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (SIGKDD) conference on Monday.

“Around the turn of the millennium, people were talking about data mining or knowledge discovery, from which SIGKDD takes its name,” he continued. “Then around 2010, you couldn’t say you were doing that anymore. You had to say you were doing big data. And now you need to say you’re doing data science. But the concept behind these changing words hasn’t really changed.”

So what does it mean? According to Ullman’s telling, data science, as it’s popularly understood, encompasses a range of disciplines, including statistics, mathematics, machine learning, artificial intelligence, data mining, knowledge discovery, domain experience, and of course, computer science and database systems research, which is Ullman’s area of expertise.

But what elements are necessary, and in what amounts, for one to lay claim to doing “data science,” or for one to claim to be a “data scientist,” for that matter? There is some debate as to the proper elements and ratios, which are commonly communicated through the graphical vehicle known as the Venn diagram.

“It turns out that every field has its own definition of data science,” Ullman said, “and it’s one that magnifies the importance of their own field, and it can be represented by a Venn diagram.”

Stanford University Computer Science Professor Jeffrey Ullman, seen in his KDD2021 presentation Monday, is a co-winner of the Turing Award in 2020

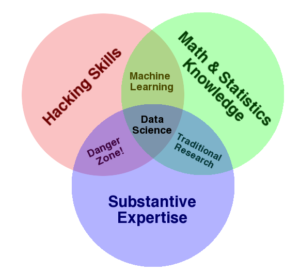

Before sharing his own Venn diagram on the elements needed in data science, Ullman took one of them to task, specifically the popular data science Venn diagram created by Drew Conway (which you can see at the top of this article). You have probably seen Conway’s Venn diagram, with three overlapping circles representing hacking skills, math and statistics knowledge, and substantive expertise (it is the first result when you Google “data science Venn diagram.”

“The reason I focus on this one is that, several times I’ve listened to statisticians presenting this very diagram as the true definition of data science,” Ullman said. “What’s wrong with it? Well, it turns out everything is wrong with it.”

Ullman listed several objections, starting with Conway’s use of the term “substantive expertise.” Ullman’s preference is for domain knowledge. But this was just a mere quibble, as Ullman was just getting started.

“Here’s the thing that really drives me nuts,” he continued. “Computer science is not just writing code. We have very many models, abstractions, algorithms–all of which make the solution of data science problems possible. A little respect would have been in order.”

Ullman also objected to the region where “hacking skills” and “substantive expertise” intersect, which Conway calls a “danger zone.”

“Conway calls a computer scientist trying to help some domain scientist a danger, if they do not function under the wise guidance of a statistician,” Ullman said. “I’m going to argue that most achievements of data science really fallen in this category, with this portion of the Venn diagram.”

While one gets the distinct impression that Ullman is not overly impressed with statisticians (or at least how they view their importance to the field of data science), he also does not want to dismiss them entirely.

“Their achievements have been many, and the tools they created have important uses in data science and computer science in general,” he said. “Many statisticians are beginning to get interested in computer science problems, and are able to make important contributions.”

For example, Ullman credited one of his Stanford colleagues, a statistician, with introducing him to a powerful data reduction technique called locality sensitive hashing. “He was able to show me something that speeds up one of the important algorithm in that field called min-hashing, by a lot,” Ullman said. “I should have been able to see it before myself. But I didn’t. He did.”

Ullman was also critical of the intersection between math and statistics knowledge and substantive expertise in Conways’ Venn diagram. “Here’s what Conway calls traditional research. Supplied statistics to a problem without writing any code,” Ullman said. “I don’t know whose tradition that is, but I hope it’s not yours. All that does is provide amusement for the statistician or the mathematician, and it doesn’t provide a solution to anything.”

Ditto for machine learning as the intersection of hacking and math/statistics. “Is machine learning really something that doesn’t apply to any domain?” Ullman asked. “Well, there have been some great achievements by people looking at the methodology in machine learning rather than applying it. I think that the reason everybody wants to engage in machine learning these days is because it’s so useful in solving problems in a variety of domains.”

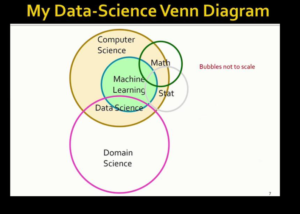

After dissembling Conway’s Venn diagram, Ullman provided his own.

“There is computer science and there are scientific domains we’d like them to affect, and somewhere in the middle is data science,” he said. “Now, machine learning is a branch of data science. It is used for a lot of work that stirred the application domains, but it also has uses in purely internal matters of computer science, often in applications that are called artificial intelligence, rather than machine learning.”

For example, machine learning is useful in detecting intrusions into computer systems, which Ullman says is a subject that fall squarely within computer science, and not in any particular application domain. Machine learning is also useful in creating general things like chat bots, which also don’t fall into any particular domain, he said.

“Now, math and statistics both have a role to play in this picture,” Ullman said, while apologizing for the size of his bubbles. “But my point is that math and stats have lots of applications in computer science. But they don’t affect domains by themselves. They do so through the algorithms that they help design and analyze.”

In some cases, mathematics and statistics are critical for proving that algorithms developed with computer science and machine learning skills work, although they aren’t actually used in the development of the algorithm itself. And not all big data problems require machine learning models to function, Ullman said.

For example, the previously mentioned locality-sensitive hashing (LSH) technique and the Flajolet-Martin algorithm, which is used for approximate counting, are not machine learning algorithms, yet they are useful for solving big data problems.

There are also claims that require precision in statistical calculations. “For example, when you claim 10% of the population is in poverty in some place, did you mean that there’s a 95% probability that the actual percentage is between 9 and 11%? Or that there is a 75% probability that is between 2% and 20%?” Ullman said. “You need to get the story right.”

However, there are limitations with the applicability of the statistical approach. For example, Ullman discussed a recent hackathon, in which participants spend a weekend searching for “something interesting” hidden in the data.

“I guess that can be very amusing as a contest,” Ullman said. “But wouldn’t it be better to encourage students to take that same data, and use it to solve a problem someone cares about? So for my own preference, I prefer the Kaggle approach, where people who really want a solution to a problem can post data sets and people compete to solve the problem for cash prizes.”

People who are prone to the statistical interpretation of data science seem to forget the experimental side of the coin, he said. “….[D]ata science is largely, even if it’s not completely so, it is largely an experimental science,” he said. “If you want to know if your idea solves a problem you were working on, then implement it, run it, and see.”

The practical empiricism of data science is on display every day via Google’s anti-spam mechanisms. The intersection of computer hacking and domain expertise would find itself in Conway’s danger zone, Ullman said. “Think of what would be lost by throwing the software away,” he said. “People would be falling into spammers traps all over the world.”

If you looked under Google’s hood, you would surely find statistical components in that spam detection engine. “But the value of these ideas is only realized through the implementation, but not directly,” he continued.

Put another way, the perfect is the enemy of the good. If data science demands experimentation as a source of constant improvement, then the role of statistics, with its heavy focus on analysis and finding the perfect approach, must merely be a supporting one.

“One of the things I learned from data science education was that the statisticians tend to think with the mind of a mathematician,” Ullman said. “That is, they’re here too much concerned with analysis, and not enough with problem solving.”

The KDD 2021 conference runs through today.

Related Items:

Why Data Science Is Still a Top Job

The Maturation of Data Science

‘Data Scientist’ Title Evolving Into New Thing