Patchwork of Data Privacy Laws Sows Confusion

The European Union’s GDPR. California’s CCPA. Brazil’s LGPD. Canada’s PIPEDA. Japan’s APPI. Every country and state seems to have its own law governing how personal data can and cannot be used, and companies are struggling to navigate the differences and adhere to their requirements.

The Chinese are not generally known for protecting the digital rights of citizens. The Chinese government’s Social Credit System, which punishes and rewards people based on their actions online and in the real world, would be considered a huge invasion of privacy in Western democracies.

Despite that perception, the People’s Republic of China actually rates a “heavy” on DLA Piper’s data protection law rating. And those laws are getting heavier with the recent draft of a new data regulation, called the Data Security Law, that would tighten rules around accessing and sharing data and promote the use of government data, among other changes.

Progress is also being made in Brazil, where the president recently signed a new national data protection law called Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados, or LGPD, that is closely aligned with the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

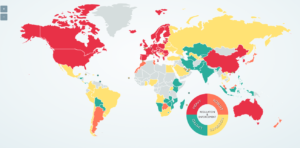

DLA Piper’s website rates every country’s data protection laws

In California, voters will be asked in three weeks to pass Proposition 24, which would replace the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) with a tougher law, called the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA). In some ways, the CPRA would be tougher than the GDPR, experts say.

“These data protection laws seem to be sprouting up almost one per week,” says Chris Strands the chief compliance officer of intSights, a provider of cyber security solutions. “Depending on where you’re sharing data and where you’re getting the data from, you may be suddenly be in violation of some data protection law, and we’re trying to add clarity around that.”

In the latest development, an agreement that allowed U.S. companies to transfer data about their European customers back to the U.S. was struck down by a European court. The Privacy Shield Framework, which was established between the U.S. Department of Commerce, the European Commission, the Swiss Administration to enable data to be shared among the countries, was invalidated in July by the EU Court of Justice.

The court stated the U.S.’s patchwork of data protection laws didn’t adequately ensure protection of EU citizens’ data. However, it did state that another mechanism for data transfers, dubbed Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs), would suffice.

The ruling leaves U.S. companies in legal limbo, Strands says. “It’s not that there’s no solution, but it’s being sorted out right now,” he says. “As you know with all these things, at a national level, it takes a long time to sort that out.”

Strands, who was a data auditor for 15 years before joining intSights, advises that U.S. companies handling the personnel data of citizens of the EU (or that of citizens from Switzerland or the UK, which are not in the EU) should look closely at their data practices.

“These business and firms need to do additional due diligence in the way they’re handling that data, just to protect themselves,” he says. “They’re going to have to do a little extra to make sure they have all the things they need in case they get an injunction that says, wait a second, you’re breaking the law here in using personal data from customers around the world.”

The best practice, Strands says, is for companies to abide by GDPR, the data law that went into effect in May 2018 to protect the data and the privacy of citizens in the 28 countries that make up the European Union (27 now that the UK left the EU in January).

Strands advocates using the GDPR as a baseline for how U.S. and Canadian companies handle their customers data, even if GDPR is not the law of the land for protecting American and Canadian citizens’ data.

“That’s a good standard to follow,” he says. “It’s a good baseline to say, yeah, we’ve measured our cybersecurity controls against the recommendations of the GDPR. That puts you at a bit of an advance in terms of protecting yourself form a liability situation.”

Data protection laws are still evolving in the U.S. and Canada, and some states and provinces have stronger laws than others. That, of course, complicates matters, especially for companies that want to stay on the right side of the law.

“It’s a bit of the Wild West, not just in the U.S., but all North America for that matter,” he says. “If you don’t have some sort of national data protection policy as a country, it’s up to the induvial states or provinces or whatever it is to take care of it.”

There is a bit of chaos at the moment, but Strands predicts things it will eventually calm down. He notes that, just as companies initially resisted the Payment Cardholder Industry Data Security Standards (PCI DSS) that implemented stronger protection of credit card data, companies will eventually come around to protecting other private data.

“Five or six years ago the attitude was, just collect everything,” he says. “Organizations were collecting and storing data, and keeping it indefinitely. But now they’re finding out that they should step back and ask, why am I collecting it?

“The rule in PCI has always been, don’t collect anything you don’t need,” he continues. “If it’s not part of business as usual, then don’t store it, don’t transmit it, don’t use it. Just leave it alone. And that’s policy I see being put into place before the questions being asked by businesses now.”

Related Items:

CPRA Poised to Replace CCPA, Bring Stricter Data Enforcement

Does the U.S. Have a Case of GDPR Envy?