Data Science Finds New Uses in Political Science

(ev radin/Shutterstock)

The intersection of public policy and public data is fertile ground for data scientists to practice their craft. Two new use cases that recently emerged in the United States are drafting political districts and predicting political unrest.

Following every decadal census, all 50 states must redraw political boundaries to ensure each Congressional district has an equal population, insofar as it’s “practical.” Hundreds of additional state and local districts are also being redrawn following the 2020 Census.

The redistricting is fraught with political danger, as there exists the potential for the new districts to benefit one party or the other. Accusations of gerrymandering are never far off, particularly when one party controls the process. Now a group of people in Minnesota are taking a novel approach to redrawing the lines in an equitable way: letting algorithms do it.

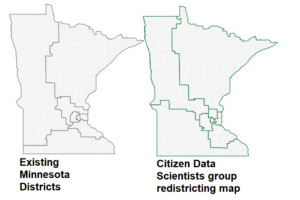

According to the (Minneapolis) Star-Tribune, a dozen mathematicians and data scientists have embarked upon a project to enable a computer model to redraw the state’s eight Congressional districts. The group, which calls itself the Citizen Data Scientists, uses the priorities set by a judicial commission as input.

Those requirements include avoiding maps that seek to protect, promote, or defeat any incumbent, candidate, or political party, according to the story. It also means maintaining voting blocks among minority communities, as well as trying to keep together population centers with shared economic, cultural or economic heritage.

“The number of combinations is astronomical,” said Sam Hirsch, an attorney who helped assemble the group, according to the story in the Star-Tribune. “A decade ago, the kinds of things we’re doing were not known and were not possible.”

Armed with a hefty amount of computing power, the group iterated through millions of maps before settling on one, which is one of five maps that the judicial commission will consider. According to Hirsch, it’s a computer-aided success story.

“The court defines the priorities, but a computer just does a better job of crunching the data and experimenting with different combinations,” Hirsch told the Star-Tribune.

Tracking Political Unrest

Researchers are also investigating the potential for algorithms to provide an early warning of potential political unrest in the United States, such as what occurred January 6, 2021. That event, which local law enforcement agencies failed to predict, could be a precursor to more political violence in the future.

One such group is CoupCast, a project at the University of Central Florida that uses machine learning techniques like gradient boosting and deep neural nets to crunch a variety of societal factors to predict the likelihood of coups and electoral violence for dozens of countries each month.

Researchers want to use AI to give them a heads-up of political unrest, such as what occured on January 6, 2021 (lev radin/Shutterstock)

According to an article in the Washington Post, the folks at CoupCast are considering running the same type of analysis for the United States, which would be a novel use.

“We now have the data–and opportunity–to pursue a very different path than we did before,” the Post quotes CoupCast’s Clayton Besaw as saying. “It’s pretty clear from the model we’re heading into a period where we’re more at risk for sustained political violence. The building blocks are there.”

This sort of sentiment analysis has become fairly common overseas. The company that is now OmniSci started out as an MIT CSAIL project to use social media posts to track the Arab Spring in 2011. Other groups that seek to protect political violence, like PeaceTech Lab, have also started to focus on the US.

The latest attempts look to go beyond social media, which some say is not a reliable indicator of looming unrest. Additional data types–such as income inequality, economic disruptions, climate change, and social-trust levels–could provide a better forecast of a political storm on the horizon, according to the Post’s story.

Related Items:

Next Up for AI: Running for Mayor

Six Data Science Lessons from the Epic Polling Failure