Internet Pioneer Vint Cerf on Shakespeare, Chatbots, and Being Human at SC21

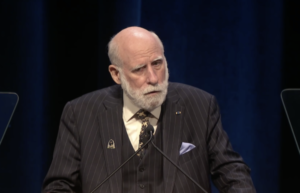

Vint Cerf, Google

Unlike the deep technical dives of many SC keynotes, Internet pioneer Vint Cerf steered clear of the trenches and took leisurely stroll through a range of human-machine interactions, touching on ML’s growing capabilities while noting potholes to be avoided if possible. Cerf, of course, is co-designer with Bob Kahn of the TCP/IP protocols and architecture of the internet. He’s heralded as one of the fathers of the Internet and today is vice president and chief evangelist for Google. (Brief bio at end of the article).

“[The] humanities ask a very simple question – what does it mean to be human? So, we try to answer that question. We study, music and poetry, we study art, languages, [and] history to try to understand how humans affect the flow of history, how their decisions and preferences and excitement and joy and anger and everything else. Then we assume that those palpable expressions shown in text and art are somehow telling us more than just simple biology. Surely, we are more than just our DNA, at least, I hope so,” said Cerf, sharing credit for that formulation of humanities goal with colleague Mike Whitmore, director of the Folger Shakespeare Library, in Washington.

The broad question posed by Cerf in his SC21 keynote (Computing and the Humanities) is how and to what extent can human-computer interactions contribute to the humanities. Language, visual art, critical thinking all made their way into Cerf’s presentation. The implied question, not answered but frequently hinted at, is to what extent will computers be tools, assistants, partners, or masters in humanities.

He began with a cautionary tale using Shakespeare’s sonnet 73 as the example in which a computer system trained on the Bard’s works is presented with an unfinished fragment of the original sonnet 73; as you may have guessed it’s able to (mostly) generate the missing text, off by just one word.

“The point I want to make is that this wasn’t simply a thing that did string matching and then plucked out the rest of the Sonnet. This is generated, based on statistical information, almost what Shakespeare wrote. The reason that’s interesting is that if we chose to provide some other preambles that were not written by Shakespeare, the system would still try its best to produce a statistically valid conclusion to the rest of the sonnet,” said Cerf. “There might be a time when you could, if you were skilled enough, you might be able to write something which is very Shakespearean at the beginning, and then let the system produce the rest of it, which you could then discover miraculously as a Shakespeare piece that no one had found before, and take a picture of and sell it as an NFT for $69 million.”

“Let’s start our adventure [by] recognizing that artificial intelligence and particularly machine learning is allowing us to experience and explore and analyze text in ways that we couldn’t before,” said Cerf. “Some people are feeling a little threatened by, by these kinds of capabilities. For example, the possibility of creating what some people will call deep fakes, whether that’s imagery, or text, which looks very credible. If you think a little bit, you’ve probably seen some websites where you can go to the website, and it produces a picture of a person, except that that person never existed. But the person looks like a real person. Why does it look like a real person? Well, it’s because the features of the image are drawn from a statistical collection of data about faces, that matches our expectations of how faces are put together.”

You can read the rest of the story at our sister site, HPCwire.