2020 Election: Five Ways to Improve the Accuracy of Polls

(chrisdorney/Shutterstock)

There has been a lot of handwringing from professional pollsters regarding the failure to predict President Trump’s victory in 2016. Not a lot has changed when it comes to the mechanisms for detecting political signals amid a whole lot of noise, which could lead to more surprises in the 2020 election. So what can pollsters do to regain the scientific accuracy they once possessed? So-called “cowboy pollsters” may have found better techniques.

The unfortunate fact is, the old methods that pollsters relied on to conducting opinion survey, which rely heavily on calling landline phones and asking voters who they plan to vote for, simply does not provide the same level of accuracy as it used to. The reasons have to do with technological and demographic changes.

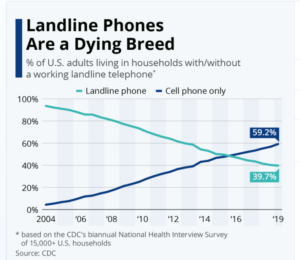

As recently as 2004, landline phones were ubiquitous in the United States, with more than 90% of households reporting having a functional landline, according to data from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. And since the bulk of those numbers were publicly listed, landline phones were a great mechanism to obtain a representative sample of American voters, which made it the standard method for conducting a political poll for decades.

However, landline use has plummeted in recent years, and now less than 40% of households have a landline, with 6.5% of households reporting that the only phone they have is a landline, according to the CDC data. The culprit, of course, are cellular phones, which are now used by 96% of adults, according to Pew Research. Unfortunately, cell phone numbers are not publicly listed, which drastically restricts their usefulness in conducting statistically valid opinion surveys.

“You’ve got to broaden the base of the people you contact,” says Glen Rabie, the CEO of Australian software company Yellowfin Business Intelligence. “If you’re just talking to 70-year-old people with a landline, that doesn’t really help you understand the entire population. So you have to be able to get to and be able to talk to the entire population, to get the views of who’s likely to vote or not.”

The question, of course, is how to get a better sample. Here are five possible methods that can help:

1. Widen the Base with Cell Phones, Email, Text, and the Web

If landline-based polling methods is essentially dead, the most obvious method may be to expand the methods of communicating with Americans. Including cell phones in political polls is one obvious method to widen the base of people participating in a poll, but the opportunity also exists to use email and the Web to reach people.

Robert Cahaly, the head of a political polling outfit called Trafalgar Group, conducts polls that enable people to respond by texts, email, and even answering questions on a website. The key is being flexible, and keeping the survey short, he says.

“We give [respondents] lots of different ways to participate–online, by text or email,” Cahaly told Politico in a recent interview. “You get one of our text polls at 7 p.m., and you can flip through it while watching TV, or answer Question 1 at 9 p.m. and answer Question 2 the next morning. That’s fine! We give you the time to participate on your schedule. We make it very easy. It takes less than three minutes if you do it all at once.”

Cahaly has run into legal trouble for his unconventional methods. In 2010, he was arrested for running illegal “robocalls” in South Carolina (automated calling, alas, is still considered illegal when targeting cell phones). But Cahaly challenged the constitutionality of the law in federal court and won.

2. Run a Panel on the Internet

Panels have long been considered a viable method for collecting information about people’s opinions. Frank Luntz, the Republican pollster and campaign strategist, has used this technique for decades, with good results.

Panels have several benefits compared to random polling, including higher response rates. They’re often cheaper to conduct, once a panel has been established. However, because of the low number of people involved, there are concerns about accuracy as people leave the panel over time. There is also a particular bias that can emerge when panelists become conditioned to giving a certain response (particularly if they are paid).

One pollster who has an innovative new twist on panels is Arie Kapteyn, who runs the USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research. His group runs the USC Daybreak Poll, which was one of the few polls to predict Trump’s victory in 2016. This year, Kapteyn has been running an Internet-based panel this year consisting of about 9,000 people.

According to the story in Politico, Kapteyn’s group selects panelists through a random drawing of a list of addresses in the US. The group pays for high-quality lists, and pays panelists about $20 for a 30-minute interview, during which they cover a wide range of topics, including politics.

Kapteyn says the online panel may help alleviate the “Shy Trump Voter” effect, which was in play in 2016 and could be in play again in 2020. “If someone on the Internet checks the box for Trump, no one is going to yell at them,” he says.

3. Run a Huge Public Survey

Traditional public political polling in the U.S. involves creating a model of likely voters, and then going out and finding a certain number of actual people who match the demographic characteristics in that model. The pollsters must spend a lot of time to make sure that model is as accurate as possible.

Usually, it doesn’t make sense to significantly increase the sample size in a random poll. With a well-constructed sample of a few thousand individuals, the statistical error can be whittled down to around 3% to 5%, but the returns diminish quickly past that, and it takes a lot of work (and money) to get the error rate much below that.

However, with everybody’s favorite mass communication device – the Internet – that brute force approach is becoming more feasible.

Yellowfin’s Rabie points to an ongoing Survey Monkey survey of the U.S. election, which has more than 640,000 respondents, as evidence that larger sample sizes could be a reliable tool in the pollster’s toolbox going forward.

“When you have small sample sizes, you have to make a lot of assumptions in the model. You have to build up this artifice that says, what does the rest of the population look like?” Rabie says. “But the more fine-grained you can get, you get more access to more electorates, to more data. And your models rely less on assumptions because you actually have better and more accurate actual data.”

That’s especially true during times like these, when we have large shifts occurring in the demographics of the American voter. “If you more access to actual live data, you’re going to be better off and be better able to predict the outcome from this election,” he says.

4. Ask Indirect Questions

Pollsters have typically taken the direct approach by asking straightforward questions, such as “Who do you plan to vote for?” But as discussed above, there are Trump supporters who will avoid giving a direct answer.

To get around this impediment, some pollsters, including Cahaly and Kapteyn, are asking questions about the respondents’ social circle. So instead of asking whether the respondent will vote for Trump, the pollsters ask who the respondents’ friends and neighbors will vote for.

Asking indirect questions can help counter the “social desirability bias” (studiostoks/Shutterstock)

“We live in a country where people will lie to their accountant, they’ll lie to their doctor, they’ll lie to their priest,” Cahaly told Politico. “And we’re supposed to believe they shed all of that when they get on the telephone with a stranger and become Honest Abe? I cannot accept that.”

This technique can also be used to strengthen the model of likely voters, and be used as a proxy for how people will vote, according to Rabie. For example, if a pollster inquires about how COVID-19 has impacted them, that can be a powerful proxy for other measures.

“Rather than a straight out ‘How will you vote?’ [you’re asking] ‘What is the thing that drives you?’” he says. “The impact of COVID is great. Have you lost your job? Have you or your family or close friends experienced an illness? Have you had a death in the family.”

By asking questions in an indirect way, a pollster can sometimes get a better indication of a person’s likelihood to vote, as well as what that vote might be, Rabie says. “It’s a simple indicator of your belief structure,” he says. “There are a range of ways in which to determine people’s propensity to vote as opposed to simply asking them ‘Will you vote and how would you vote?’”

5. Go Full Cambridge Analytica

We live in an age in which every Web page we visit, every click of the mouse or touch of the screen is scrutinized and analyzed to the n-th degree. Facebook alone is said to track 30,000 variables for each person who uses its social media platform. With all this data and high-powered analytics, how is it that we have lost the ability to detect the signal of presidential preferences?

While the national polling firms largely failed to detect the signal of the 2016 election, the same cannot be said of the political campaigns themselves, which conduct their own polling and use their own methods. In 2016, the Trump campaign benefited from the work of Cambridge Analytica, which first was associated with Senator Ted Cruz’s primary campaign before working for Trump for the general election.

Cambridge Analytica has been heavily criticized for taking data that Facebook ostensibly collected for use by advertisers and instead using it to conduct a highly targeted political campaign. According to Rabie, the same sorts of techniques could be leveraged to detect the political leanings of Facebook users at the same individual level.

“I think there are statistical methods and methodologies out there that would be able to do this very, very well, based upon sentiment analysis out of Facebook and Twitter,” Rabie says. “The question really is, do pollsters or does anyone want to do that, to be seen to be doing that? That’s the question.”

The cost associated with this approach would also be relatively high, especially compared with using telephones.

Related Items:

Systemic Data Errors Still Plague Presidential Polling

Six Data Science Lessons from the Epic Polling Failure

Trump Victory: How Did the National Polls Get It So Wrong?