Documentary Probes the Human Face of Big Data

The huge impact that big data analytics is having on how we interact with each other and learn about the world is the topic of a new PBS documentary airing tonight at 10 p.m. locally titled “The Human Face of Big Data.”

The one-hour show, which shares a title with the 2012 book co-authored by Rick Smolan (the executive producer of the film), will dive into a variety of emerging uses of big data, ranging from how connected data is impacting healthcare to how babies learn language. It also looks into the dark side of big data, and the possible repercussions it has on privacy.

Judging from trailers on PBS’ preview page, viewers will be treated to a feast of big data visualizations, as well as commentary from industry leaders, like Jack Dorsey, the founder of Twitter (NYSE: TWTR) and Square; Aaron Koblin, the co-founder and CTO of Verse; Jer Thorp, a data artist for the New York Times; MIT professor Deb Roy; Shwetak Patel a McArthur Fellow; and Linda Avey of 23andMe.

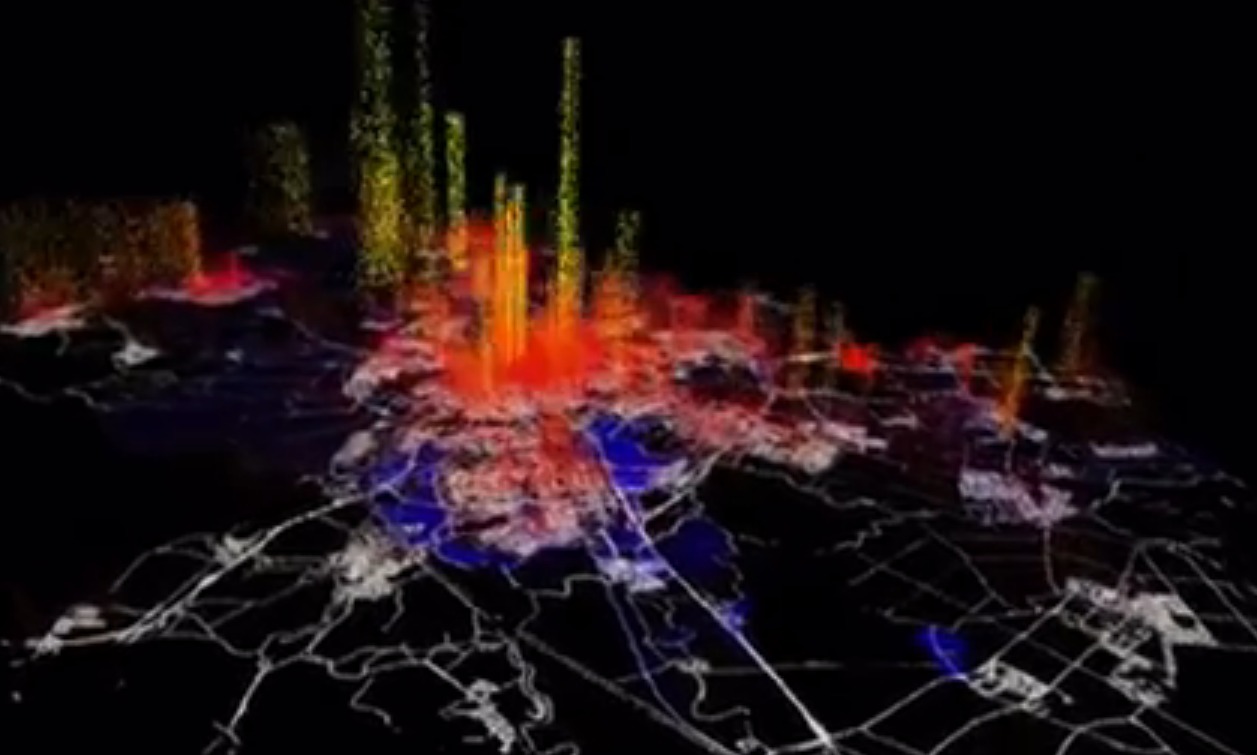

Stunning visualizations, such as the pattern of text messages sent during an evening in Amsterdam (see fig.01) and the course of jet paths over the United States, show how data can not only entertain us, but tell us something we didn’t previously know about ourselves.

fig.01

“It takes people or programs or algorithms to connect it all together, to make sense of it and that’s what’s important,” Dorsey says in a trailer. “…[E]very single action that we do in this world is triggering off some amount of data, and most of that data is meaningless until someone adds some interpretation of it, or someone adds a narrative around it.”

You probably haven’t yet heard of something called a “wordscape,” but that concept is providing new insights in the development of language in babies. Roy came up with the concept after analyzing more than 800 million words of speech uttered in his home after his son was born. The words and video were captured by cameras Roy had installed in every room, and thereafter transcribed–presumably using a well-trained natural language processing algorithm.

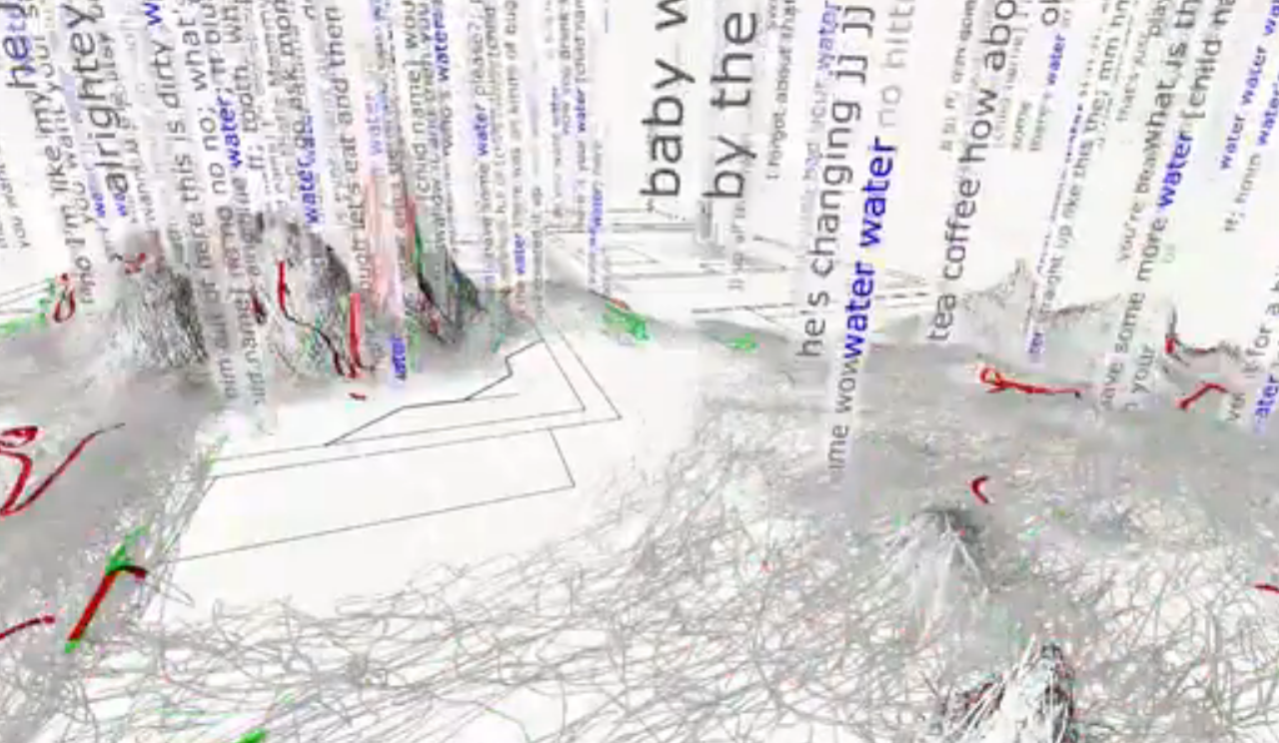

It turns out that those “wordscapes”—which are visualizations that show relevant context (including place and time) around the use of a word first time (see fig.02)—have more predictive power for learning new words than the frequency that a baby hears a word. That insight wouldn’t have been possible without wordscapes, says Roy, who’s also the chief media scientist at Twitter.

fig.02

“It’s like we’re building a new kind of instrument,” Roy says in a trailer, “like we’re building a microscope and we’re able to examine something that is around us, but it has structure and pattern and beauty that are invisible without the right instruments and all of this data is opening up our ability to perceive things around us.”

The amount of data we’re generating is mind boggling. According to the film, humans generate as much data every two days as was generated from the dawn of humanity through 2003. Every day, we’re exposed to as much information as our 15th century ancestors were exposed to in a lifetime.

All that data can tell us something, says Jay Walker, curator and chairman of TEDMED. “We’re now collecting exabytes and petabyte of data and we’re looking through that data set using incredibly powering algorithms to see what we were never able to see before,” Walker says. Big data doesn’t impact one issue, but all issues, he says. “[W]e’re going to have to think as a community. There’s so much chance to improve the quality of life.”

Another segment unearths some surprising facts about the criminal justice system. Two researchers, Laura Kurgan of Columbia University and Eric Cadora of the Justice Mapping Center, used geographical information systems (GIS) to visualize incarceration patterns for residents of Brooklyn.

fig.03

By mapping the home addresses of those who leave for prison as well as those who return from prison (fig.03), the researchers discovered there’s a 35-block area of Brooklyn where residents have a disproportionate propensity to be represented in the city’s criminal justice system.

Considering the millions of dollars spent to house those people, the researchers asked if there wasn’t a better use for the funds. Those questions might not have been asked if the patterns displayed in the visualization weren’t so stark. “The point is not to look at tons and tons of data, but what are the stories that come out it,” Kurgan says in a trailer.

The rise of wearables also has the potential to not only impact our individual health. “There’s company right now in Boston that knows you’re going to get depressed two days before you get depressed,” Smolan says. The software does it by monitoring your activity, such as the number of messages you send out and where you physically go.

The show also covers the dark side of big data—the snooping by giant corporations and our government. “Today it’s nearly impossible to be truly anonymous,” Joi Ito, the director of the MIT Media Lab, says in a trailer. “That’s one of the key challenges of big data–it has so much opportunity for both good, and for also really screwing up our system.”

The Human Face of Big Data airs at 10 p.m. locally on PBS. For more information, see www.pbs.org/program/human-face-big-data.

Related Items:

Big Data Spreading Everywhere Like Air, Deloitte Says

Big Data Really Freaks This Guy Out