Inside the Panama Papers: How Cloud Analytics Made It All Possible

Image source: International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

In late 2014, an anonymous person offered to send a German journalist 11.5 million encrypted documents detailing the structure of offshore business entities created and managed by a Panamanian law firm in the world’s most notorious tax havens. The massive data set was simply too big for one reporter to comprehend. But thanks to the power of big data analytics running in the cloud, a large team of journalists started piecing it together.

This is the story of how the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) worked with the Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ), Germany’s largest daily newspaper, to analyze the data known as the Panama Papers. The ICIJ investigation (https://panamapapers.icij.org) surfaced unsavory connections between powerful politicians, business owners, banks, and offshore businesses, which the ICIJ alleges are used to cover up tax evasion and other financial crimes.

The Panama Papers has already led to the resignation of Iceland’s prime minister and the head of a Chilean-based anticorruption group. It’s also raised questions about the financial dealings of others, including Russian and Chinese leaders, Argentinean soccer stars, and Saudi Arabian royalty. More stories based on the ICIJ’s investigation are slated for the weeks to come, and next month the public will have access to ICIJ’s entire Panama Papers database.![]()

The Panama Papers is essentially a full data dump from Mossack Fonseca, the Panama-based law firm that’s been said to be the fourth largest creator of offshore businesses in the world. The treasure trove consists of 2.6TB of data, including relational database files, emails, and various types of documents about the 215,000 offshore bank accounts and shell companies that the law firm and its predecessors created for thousands of individuals between 1977 and 2015.

Setting up the systems that would enable ICIJ journalists to pour through this massive data set was the responsibility of the ICIJ’s Data and Research Unit Editor, Mar Cabra. In an interview with Datanami, the Spanish journalist discussed the technical challenges that the Panama Papers represented, and the practical solutions that were implemented.

An ‘Impossible’ Challenge

As is usually the case in data analytics projects, most of the work involved preparing the data. There were two main types of data that ICIJ had to deal with: structured database files, and unstructured documents.

The anonymous source gave SZ, and subsequently ICIJ, a copy of Mossack Fonseca’s entire internal database, which contained the names of the shell companies, and the names of the companies’ officers, shareholders, intermediaries, and beneficiaries. This was critical data, but without the database schema, it was difficult to piece it together. One of ICIJ’s tech experts spent months essentially reverse-engineering the database to make it searchable, Cabra said.

The database presented a challenge, but extracting information from the unstructured documents was even harder. “That was a real nightmare, trying to do OCR [optical character recognition] on all those documents. That’s what really took time,” Cabra said. To speed things up, the ICIJ set up 30 to 40 servers in the Amazon cloud. “We did parallel OCR to process the documents faster,” Cabra said.

Once the database files and unstructured data were prepared, ICIJ was ready for the next step. For the bulk of the analysis that would be conducted by ICIJ’s affiliated reporters around the world, the group used the Linkcurious Enterprise collection of analysis tools from Linkurious and the Neo4j graph database from Neo Technology.

Making the data availed over an encrypted Web connection enabled hundreds of reporters to work simultaneously. “It would be impossible to do the biggest collaboration in journalism history without this technology,” Cabra said. “But having the tools in the cloud allowed us to bring up a team of more than 370 reporters that worked together the same project and the same data.”

Graphing Magic

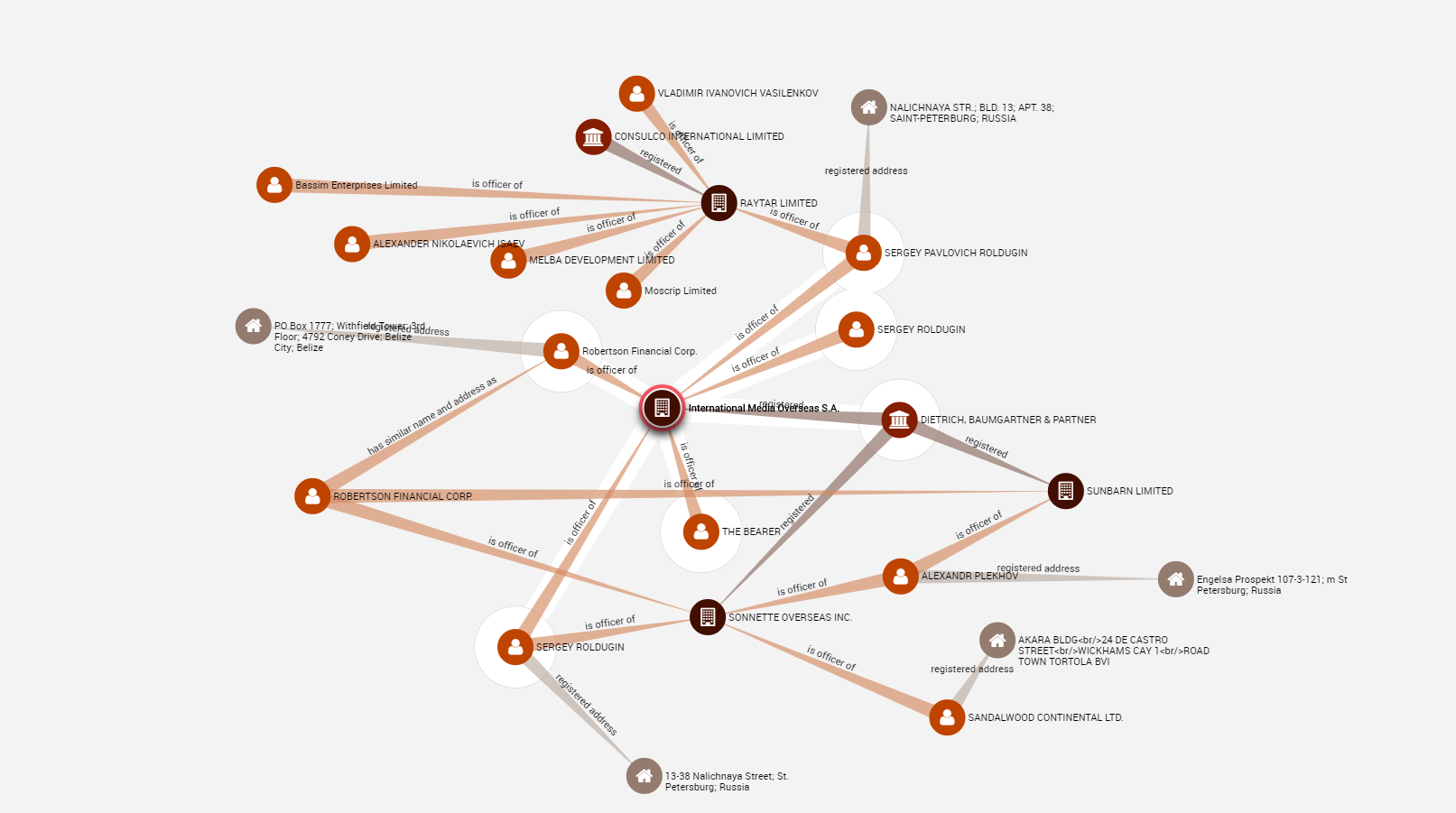

After reconstructing the database schema, the ICIJ used the open source extract, transform, and load (ETL) tool from Talend to load the data into Neo4j. The graph database consisted of the names and addresses of the 215,000 business entities that Mossack Fonseca had created, as well as the names of the principles and intermediaries involved. Each entity had at least three individuals attached to it, resulting in a graph with about a million nodes. It’s not huge by graph database standards, but plenty big enough to require big data tech.

A screenshot of the live Panama Paper graph available on Linkurious’ website.

Once the database was set up, it was a simple matter to install and configure Linkurious to essentially provide a GUI (graphical user interface) atop the database. Having the visual depiction of the graph of names and addresses was critical in making sense of the data, especially for non-technical reporters.

“That was really key,” Cabra said. “Sometimes when you search documents, you don’t see patterns of who’s connected to who. It’s very difficult. Our brains are not wired to visually see graphs.”

While some of ICIJ’s reporters are tech-savvy, many of them are not. But that didn’t really matter, because the Linkurious interface is so easy to use, Cabra said.

“A lot of reporters actually thought that Linkurious was doing magic,” she said. “They said ‘Oh my God, now I can see it so clearly. This person is connected to this person and I had missed this connection before.’ It was very good to actually see how people connected among themselves and to the companies.”

More sophisticated users could submit queries directly against the graph database using Cypher, Neo4j’s query language. But most opted to use the GUI.

“With Linkurious, I have to say, everybody understands how to connect dots basically,” Cabra said. “Without graph visualization, seeing that would have been very labor intensive….The reality is, when we’ve done that before we’ve missed things. With this, everything is grouped together, and you just have to click on the dots, so to speak, to see who’s behind it.”

Cabra set up a second platform to allow reporters to search the unstructured documents that had been digitized. This system was based on the Apache Solr search engine and was hooked up to an open source discovery tool called Project Blacklight.

The Panama Papers has connected 140 politicians from more than 50 countries to offshore companies in 21 tax havens (image source: ICIJ)

“That was basically a search engine where reporters were able to just put a term into a search box and get results,” Cabra said. “We had facets to allow for filtering the data, or downloading them or previewing them in the app.”

Reporters from various countries had no trouble entering names of prominent individuals into Blacklight and seeing if they matched up against data the Mossack Fonseca files. To speed things up, Cabra’s team modified Blacklight to enable reporters to submit a spreadsheet full of names to the search engine, and get a spreadsheet back with the results.

“That actually allowed us to mine the data much faster instead of having to type in the name,” she said.

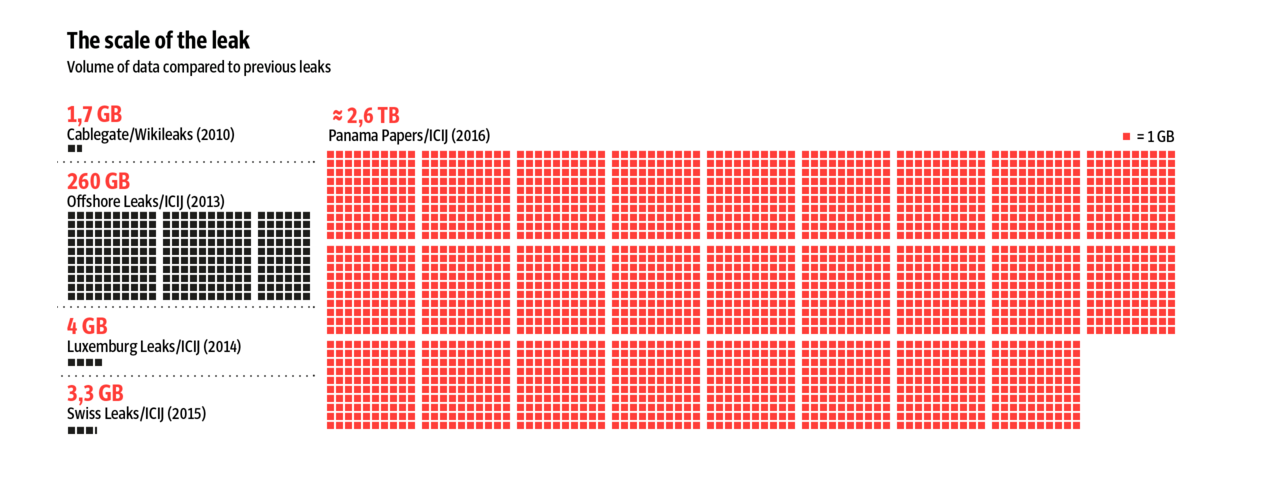

Building on Leaks

The sheer size of the Panama Papers makes it unique. At 11.5 million documents, it’s roughly 10 times bigger than the data leaked by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. At 2.6TB, it’s roughly 1000 times bigger than the leaked cables amassed by Julian Assange known WikiLeaks. Snowden tweeted this week that the Panama Papers represent “the biggest leak in the history of data journalism.”

It’s worth noting that this isn’t the first time ICIJ has done something like this. In fact, it’s the third time, and it’s the second time it’s used graph tools.

In 2013, the ICIJ published the results of its so-called Offshore Leaks investigation, which involved data from 10 offshore jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands and the Cook Islands. Then in 2015, the ICIJ was involved in the so-called Swiss Leaks investigation, which was based on 60,000 files that were leaked from the Swiss bank HSBC about more than 100,000 clients from the years 1988 to 2007.

The size of the Panama Papers dwarfs all other leaks (Source: Süddeutsche Zeitung)

The Offshore Leaks project showcased the limitations of ICIJ’s technical capabilities. The core team of reporters who worked on that project each had their own hard drive, which made sharing data difficult. “It was not scalable,” Cabra said. “That’s why they hired me to actually distribute the data around and help with queries for journalists.”

The Neo4j and Linkurious systems were in place to assist with the Swiss Leaks investigation, which was primarily conducted atop Excel files. Going forward, Cabra plans to continue scaling ICIJ’s data processing capabilities, and combining data sets to enable more links to be established and more suspicious activity exposed.

“We’re actually seeing a lot of connections between Swiss Leak and the Panama Papers,” Cabra said. “We’re building a macro database with all the databases and links, so they’re all interconnected, or at least searchable in the same place…We know that by not having all this data in one pace and searchable in the same place, we may be missing stories.”

Data Democratization

Emil Eifrem, the CEO of Neo Technology, says the Panama Papers represents a turning point in the democratization of data analytics.

ICIJ Data and Research Unit Editor Mar Cabra

“If anything else, this data leak makes it strikingly clear how important it is that highly scalable data analysis be made available to everyone: whether that’s a startup trying to disrupt a long-established incumbent or a small gang of investigative journalists that need to make sense of the biggest data leak in history,” Eifrem writes in his blog.

At the end of the day, ICIJ is all about data transparency. Tax havens exist for the sole reason to hide assets and conceal the information that would allow authorities to trace them. Now that ICIJ has gotten a taste for how the power of big data technology can deliver data transparency, there’s no telling where it might end.

“We believe that by making the data public, we’re helping not just the curiosity of the public, but we’re helping law enforcement, we’re helping NGOs and researchers, and tax agencies who want to investigate taxpayers that don’t pay taxes,” Cabra says. “I think that we have just scratched the surface on how we can analyze the graph data.”

Related Items:

Documentary Probes the Human Face of Big Data

How Big Data Can Help the Sick and Poor